Features of the Seafloor |

||

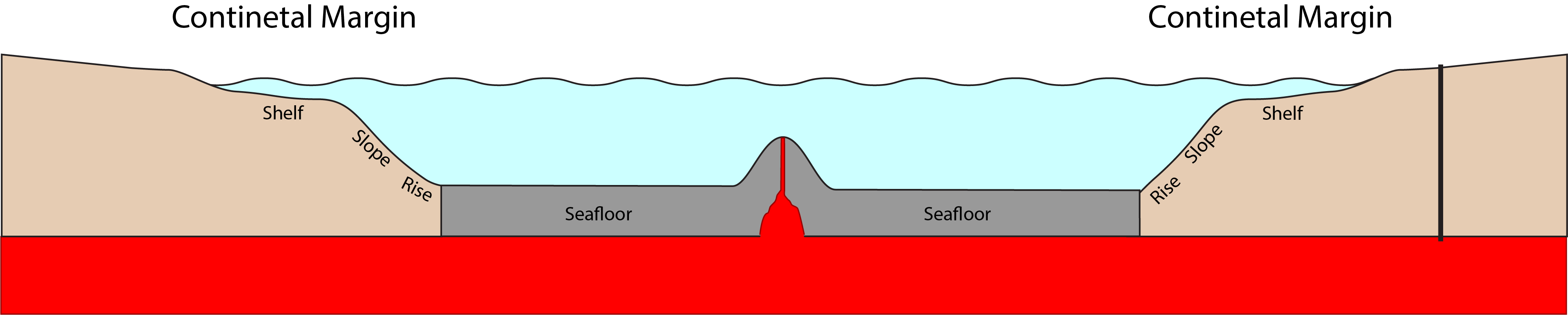

Passive margins are also called Atlantic-type margins. Recall how continents are rifted apart: Continental crust is stretched and rifted, then the spreading center creates oceanic crust between the two continental crusts. These margins ace the edges of diverging tectonic plates. As a result, there is very little volcanic or earthquake activity is found in these areas.

Examples: The east coast of North America & South America, west coast of Europe and Africa.

Image source: Sonjia Leyva, own work, © 2020.

![]()

What plate boundary is in between the continents listed above? What type of boundary is it?

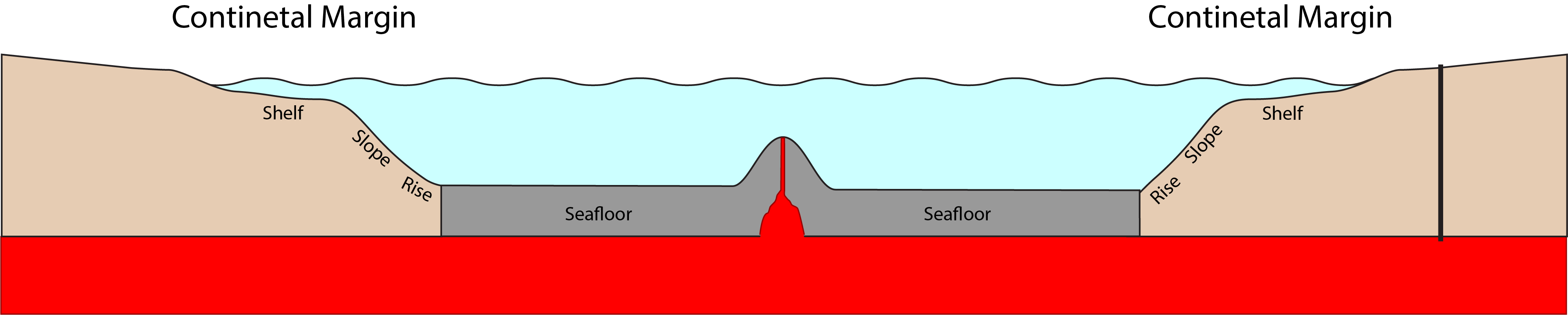

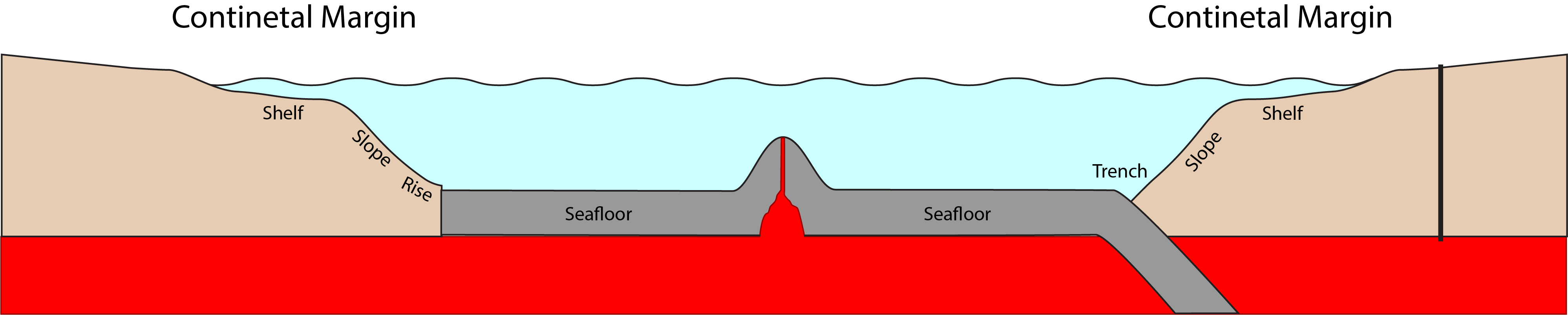

Active margins AKA as Pacific-type margins, and are either located near the edges of converging plates (subduction zones) or a transform plate boundary. This proximity to a plate boundary results in lots of volcanic and earthquake activity.

Examples: The west coast of North America, Mexico, South America, and the east coast of China & Japan.

Image source: Sonjia Leyva, own work, © 2020.

Image source: Sonjia Leyva, own work, © 2020.

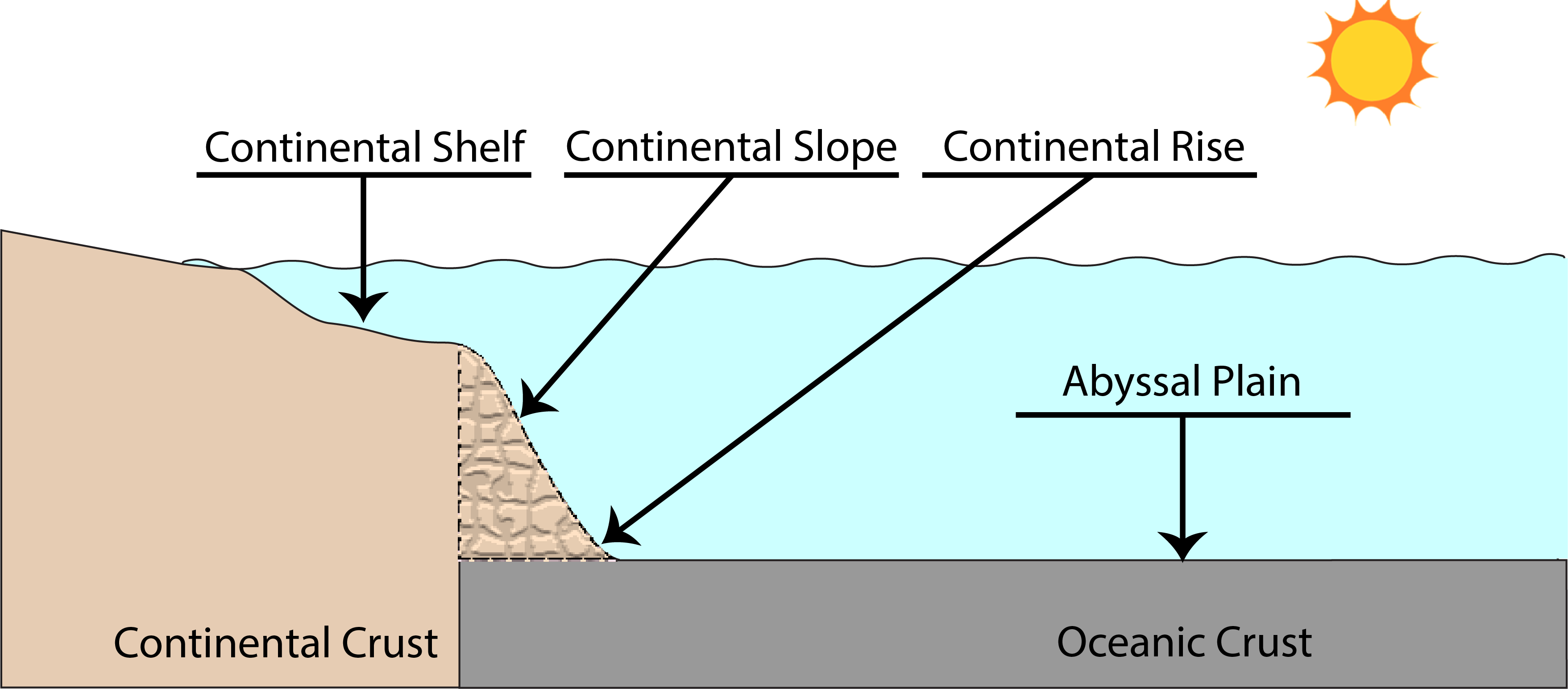

Continental Shelf |

Continental Slope |

Continental Rise |

|---|---|---|

|

The continental shelf is the top of the continental crust submerged beneath the waves and is conveniently located at the margins of the continents. Most shelves are relatively flat with an average width of 65-100 kilometers (see discussion above). Covering the continental crust on the shelf is a thick layer of marine sediments; mostly fine sands, silts, and clays derived from the continent. |

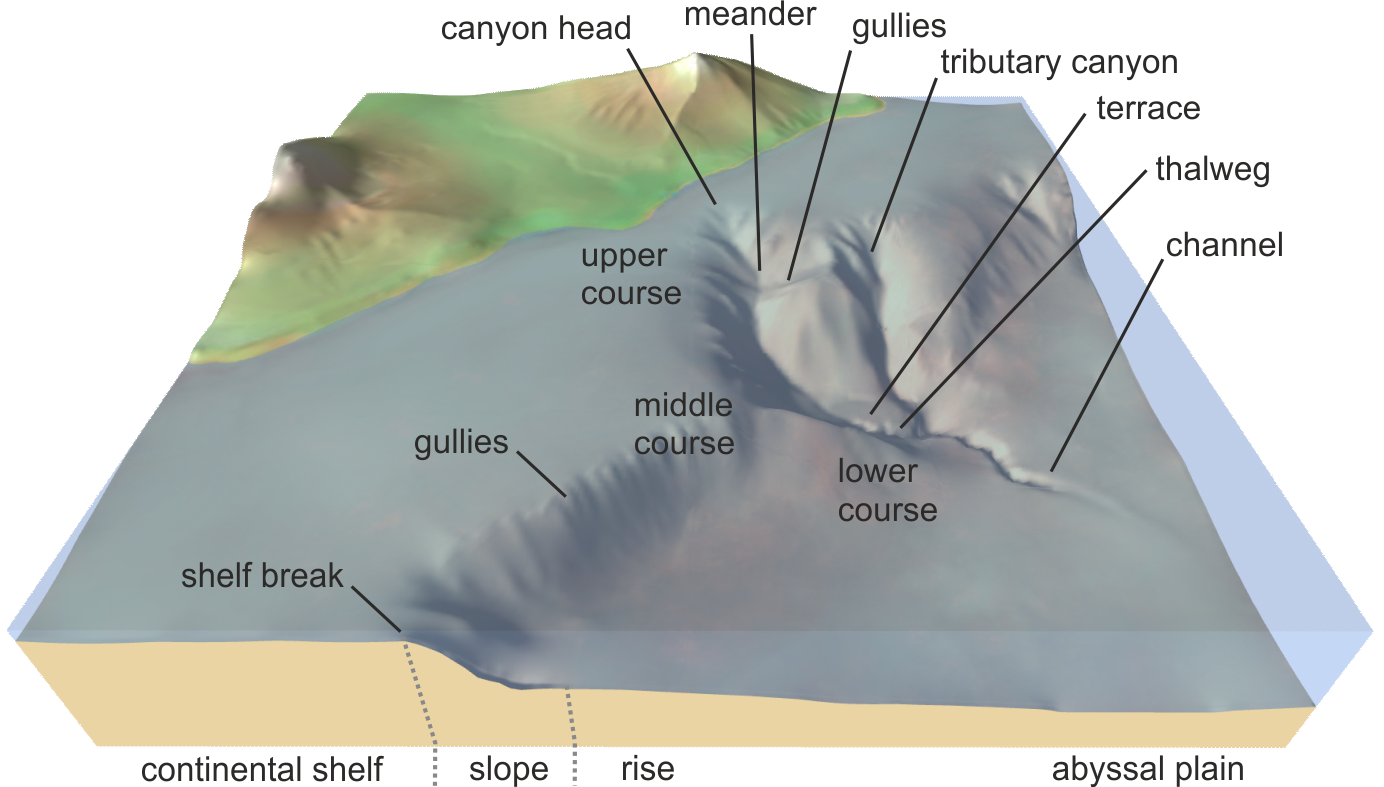

The continental slope is comprised of sediment that slides off the continental shelf, over the side, and onto the deep seafloor. Carved into the slope are submarine canyons. These canyons are formed by rivers and look and function similar to those on land. |

The continental rise is a bridge between the continental slope and the abyssal plain. Submarine fans form in this region. Continental rises are only found where trenches are absent; when a trench is present the slope just descends into the trench. |

Submarine canyons form in the same way terrestrial canyons do: from river erosion. When the river enters the sea, it keeps moving, producing a current of water moving towards the open ocean. This current also carves out a channel on the continental shelf that extends to the shelf break, when it begins to carve out a canyon.

Turbidity currents are similar to snow avalanches as they are a tumbling flow of water and sediment that rushes down the canyon to the deep seafloor. Once on the seafloor, the sediment stops and is deposited in deep-sea (submarine) fans. The heavier sediment is deposited first, then the medium, then the finest, producing a sequence called graded bedding.

Image source: "Submarine canyon.png" by David Amblas is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

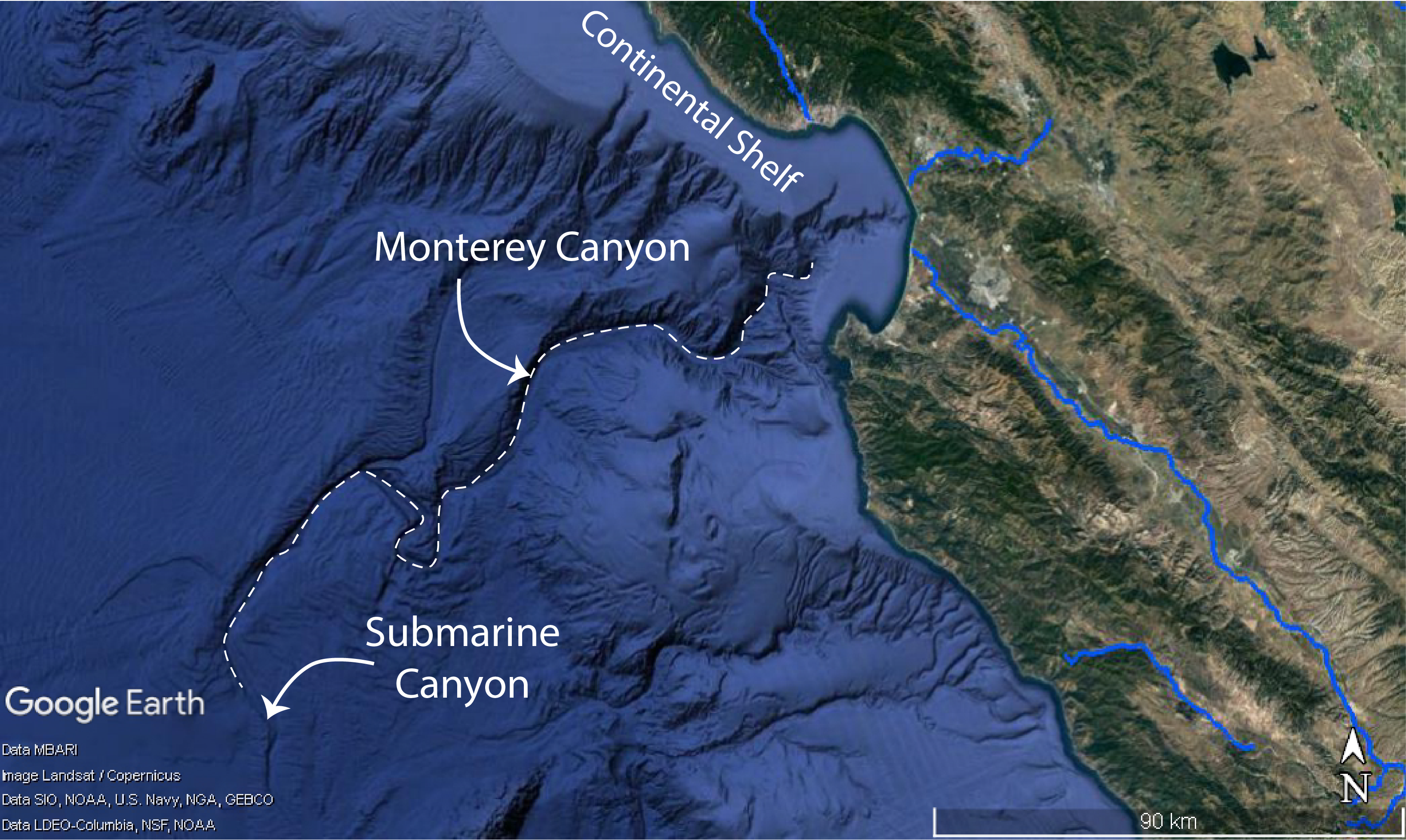

Below is an image of the Monterey Canyon, located just west of Monterey Bay. Not that it's not straight but wiggles around, just like a terrestrial canyon.

Image source: "Satellite Imagery" Google Data: MBARI, SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, IBACO, LEDO-Columbia, NFS by is in the Public Domain

Sometimes it's helpful to visually see what's going on. Watch these two videos, "Turbidite Transport: Sediment's Journey" by OceanLeadership, and "Vertical Sorting / Graded Bedding Demonstration" by GazdonianProductions.

As you do, note the following:

copyright Sonjia Leyva 2022 |

|